As the dust from what has been a hard-fought election campaign in Thailand settles, many Thais may be rubbing their eyes and asking, 'what just happened?'.

Most of the opinion polls published before the election predicted a win for the progressive People's Party. Some suggested it would get more than 200 seats in parliament, a significant improvement on its already impressive 2023 result when it won 151. Few polls put the party of Prime Minister Anutin Charnvirakul ahead.

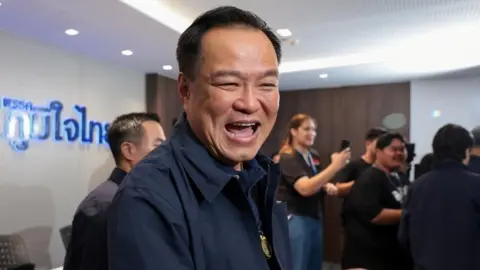

Yet once most of the votes had been counted, it was clear Anutin had achieved a stunning victory, and the young reformists had suffered a big setback. With a projected share of more than 190 seats, the path of Anutin's Bhumjaithai party is clear to form the next government, albeit with coalition partners.

So why did a youthful, progressive party with an imaginative and tech-savvy campaign do so poorly compared to a transactional, old-style party with little ideological identity aside from strong loyalty to the monarchy?

A Harder Race for the Reformists

The mixed voting system played a part. People in Thailand cast two ballots, one for a candidate in their constituency and one for the party they prefer.

At the national level, the People's Party, with nearly 10 million votes, did much better in the party list than Bhumjaithai, with just under six million votes, although this was still a big drop compared to the more than 14 million Move Forward, the previous incarnation of the People's Party, won in 2023.

But the party list accounts for only 20% of the 500 seats in parliament. As many as 80% of the seats are allocated by local contests, where whichever candidate get the most votes in each constituency wins the seat on a first-past-the-post basis.

This is where the People's Party, which is relatively new and urban-based, is weaker because it lacks rural networks. Bhumjaithai, by comparison, is a past master at using its substantial resources to win local power-brokers to its side.

Anutin has used the defections of political veterans from other parties to grow Bhumjaithai from a medium-sized provincial movement which won only 51 seats in 2019 to a national-level election-winning powerhouse today.

It was also harder for the reformists to distinguish themselves on a single issue this time. In 2023, after nine years being ruled by the stern, avuncular Prayuth Chan-ocha, the general who led the 2014 coup, there was a broad yearning for change. This captured the imagination of the public, and there was a last-minute wave of support for them.

In this election, there was no such defining issue, and the party had been forced to drop its campaign to amend the harsh lese majeste law after this was used by the courts to justify dissolving Move Forward and banning its leaders from politics.

Anutin was also able to coalesce conservative support around his party, as opposed to having their voters split among several parties in 2023. His strident nationalism over the border conflict with Cambodia, his staunch support for the army, and his intense loyalty to King Vajiralongkorn all defined him clearly as the standard-bearer for Thai conservatism.

Another big factor was the steep decline in the fortunes of Pheu Thai, the once unbeatable election machine backed by former prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra. It came second in 2023 with 141 seats but is likely to see that total halved this time round after past political turmoil.

With election dynamics shifting and obstacles for reformist parties increasing, the latest election results reflect a complex political landscape in Thailand, marking a new chapter for both the Bhumjaithai party and the potential future of reform movements in the nation.