Tanisha Singh is preparing for work when she realizes she's out of tomatoes while cooking lunch. With local vegetable vendors closed, she quickly orders through a delivery app, receiving her tomatoes in just eight minutes. This level of convenience is a common reality in Delhi and other major Indian cities, where groceries, books, and electronics can be delivered to users' doorsteps almost instantaneously.

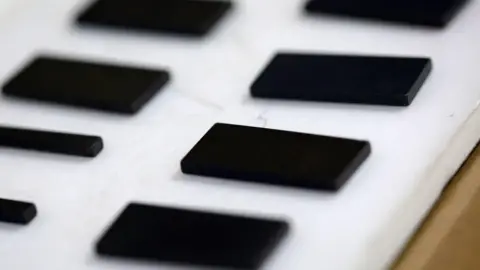

Quick-commerce companies like Blinkit, Swiggy, Instamart, and Zepto utilize 'dark stores'—small, strategically located warehouses within residential neighborhoods allowing for rapid deliveries. Unlike traditional retailers that rely on large supermarkets, these platforms operate from local storage units, arranging items for swift retrieval rather than consumer browsing. A recent visit to a 'dark store' in northwest Delhi showcased the efficiency of this system, with workers quickly fulfilling orders using a system designated for speed.

Delivery operations, however, present challenges. Riders like Muhammad Faiyaz Alam often face pressure to complete numerous deliveries daily while navigating the dense urban landscape of Delhi. Income instability is a common concern; Alam averages 40 deliveries a day, but earnings fluctuate significantly based on several factors.

As competition among companies intensifies, the focus on ultra-fast delivery times has led to mounting stress for gig workers. A recent strike highlighted dissatisfaction among delivery personnel regarding income and working conditions. While many urban consumers have adapted to quick-commerce culture, growing awareness of workers’ challenges may reshape the landscape moving forward.

Despite the convenience, quick-commerce remains a small segment of India’s retail market, and profitability has proven elusive due to aggressive competition and consumer price sensitivity. The conversation around labor practices and the sustainability of such rapid delivery models is increasingly urgent, prompting consumers like Singh to recognize the labor behind the convenience of modern grocery shopping.

Quick-commerce companies like Blinkit, Swiggy, Instamart, and Zepto utilize 'dark stores'—small, strategically located warehouses within residential neighborhoods allowing for rapid deliveries. Unlike traditional retailers that rely on large supermarkets, these platforms operate from local storage units, arranging items for swift retrieval rather than consumer browsing. A recent visit to a 'dark store' in northwest Delhi showcased the efficiency of this system, with workers quickly fulfilling orders using a system designated for speed.

Delivery operations, however, present challenges. Riders like Muhammad Faiyaz Alam often face pressure to complete numerous deliveries daily while navigating the dense urban landscape of Delhi. Income instability is a common concern; Alam averages 40 deliveries a day, but earnings fluctuate significantly based on several factors.

As competition among companies intensifies, the focus on ultra-fast delivery times has led to mounting stress for gig workers. A recent strike highlighted dissatisfaction among delivery personnel regarding income and working conditions. While many urban consumers have adapted to quick-commerce culture, growing awareness of workers’ challenges may reshape the landscape moving forward.

Despite the convenience, quick-commerce remains a small segment of India’s retail market, and profitability has proven elusive due to aggressive competition and consumer price sensitivity. The conversation around labor practices and the sustainability of such rapid delivery models is increasingly urgent, prompting consumers like Singh to recognize the labor behind the convenience of modern grocery shopping.