JUNEAU, Alaska (AP) — Storms that battered Alaska’s western coast this fall have brought renewed attention to low-lying Indigenous villages left increasingly vulnerable by climate change—reviving questions about their sustainability in a region facing frequent flooding, thawing permafrost, and alarming erosion. The onset of winter has impeded emergency repair and cleanup efforts following two October storms, including remnants of Typhoon Halong, which devastated several communities. The hardest-hit villages, Kipnuk and Kwigillingok, face prolonged dislocation and uncertainty about their future viability.

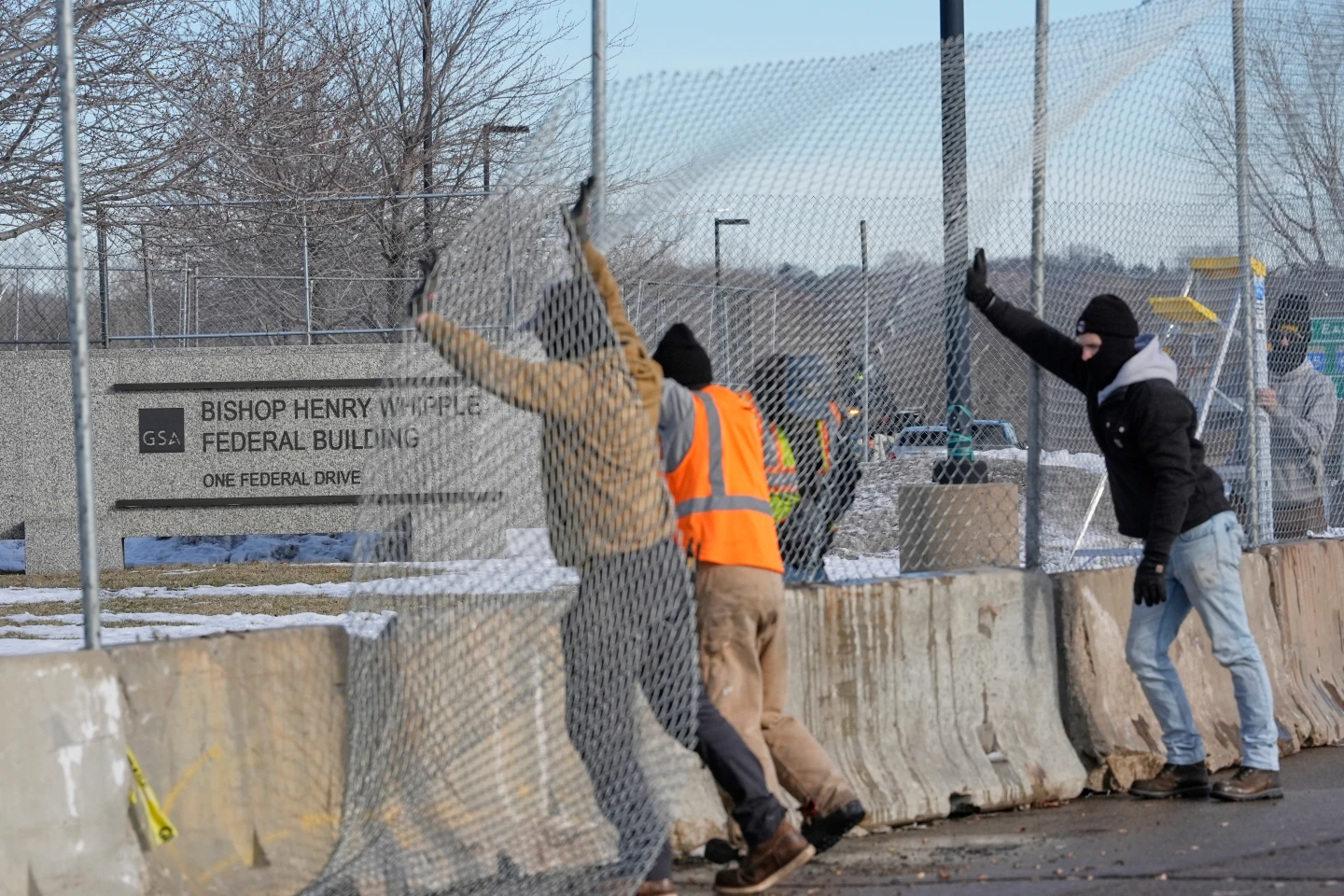

Already seeking relocation before the storm, Kwigillingok grapples with the daunting reality that such moves can take decades and lack centralized coordination or funding. The previous administration's cuts to protective grants have further complicated recovery efforts. State emergency management officials, like Bryan Fisher, emphasize the importance of bolstering infrastructure to safeguard communities while they evaluate longer-term solutions.

Alaska is warming faster than the global average, and a report from the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium highlights the vulnerabilities faced by 144 Native communities—from erosion and flooding to thawing permafrost. Coastal populations are especially at risk due to diminishing Arctic sea ice, leading to increased damage from storm-driven waves. Thawing permafrost further exacerbates coastal erosion as loose soil becomes more susceptible to washing away.

The damage from Typhoon Halong's remnants led to significant losses, including an estimated 700 homes destroyed or severely impacted; tragically, one individual lost their life, with two others missing. The options available for at-risk communities are limited and costly, with an estimated need of $4.3 billion over the next 50 years for adequate climate resilience strategies.

Authorities have attempted to establish new programs for relocation; however, inconsistent federal support raises concerns over long-term sustainability. Resilience strategies include reinforcing infrastructure, moving to higher ground, or total relocation. But, as director Sheryl Musgrove of the Alaska Climate Justice Program notes, many villages like Kipnuk and Kwigillingok "don’t have that kind of time." With ongoing uncertainties regarding federal assistance, community leaders advocate for changes in governmental support systems to better address the climate crisis threatening their homes.

Already seeking relocation before the storm, Kwigillingok grapples with the daunting reality that such moves can take decades and lack centralized coordination or funding. The previous administration's cuts to protective grants have further complicated recovery efforts. State emergency management officials, like Bryan Fisher, emphasize the importance of bolstering infrastructure to safeguard communities while they evaluate longer-term solutions.

Alaska is warming faster than the global average, and a report from the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium highlights the vulnerabilities faced by 144 Native communities—from erosion and flooding to thawing permafrost. Coastal populations are especially at risk due to diminishing Arctic sea ice, leading to increased damage from storm-driven waves. Thawing permafrost further exacerbates coastal erosion as loose soil becomes more susceptible to washing away.

The damage from Typhoon Halong's remnants led to significant losses, including an estimated 700 homes destroyed or severely impacted; tragically, one individual lost their life, with two others missing. The options available for at-risk communities are limited and costly, with an estimated need of $4.3 billion over the next 50 years for adequate climate resilience strategies.

Authorities have attempted to establish new programs for relocation; however, inconsistent federal support raises concerns over long-term sustainability. Resilience strategies include reinforcing infrastructure, moving to higher ground, or total relocation. But, as director Sheryl Musgrove of the Alaska Climate Justice Program notes, many villages like Kipnuk and Kwigillingok "don’t have that kind of time." With ongoing uncertainties regarding federal assistance, community leaders advocate for changes in governmental support systems to better address the climate crisis threatening their homes.