Reem al-Kari and her cousin Lama are searching through dozens of photos of children spread out on a desk. Lama thinks she spots one with a likeness to Karim, Reem's missing son.

Karim was two-and-a-half when he and his father disappeared, in 2013 during Syria's civil war, as they ran an errand. He is one of more than 3,700 children still missing since the fall, 10 months ago, of the Assad dictatorship. He would now be 15.

Are his eyes green? asks the man behind the desk, the new manager of Lahan Al Hayat, a Syrian-run children's shelter that was established by Asma al-Assad in 2013. He compares photos of Karim aged two with those the women have picked out.

Lahan Al Hayat is one of the several Syrian childcare facilities used to hold children of detained parents during the civil war. Instead of re-homing these children with family, they were kept in orphanages and utilized as political tools. Some were falsely registered as orphans, complicating efforts to track them down.

New investigations reveal that SOS Children's Villages International, a major Austria-based charity, operated numerous orphanages that accommodated these children, often without proper documentation. This charity reportedly received significant funding from international donors, yet oversight was minimal, allowing for tragic outcomes.

Whistleblowers within the organization allege that children were accepted regardless of their backgrounds to secure more funding. Some former staff members described the organization's leadership as being under direct influence from the Assad regime.

SOS has officially acknowledged that some children were accepted without proper documentation but maintain that there was no formal relationship with the regime. Yet, the data shows that the charity cooperated with the Syrian government without adequately checking on the children’s safety or wellbeing once returned.

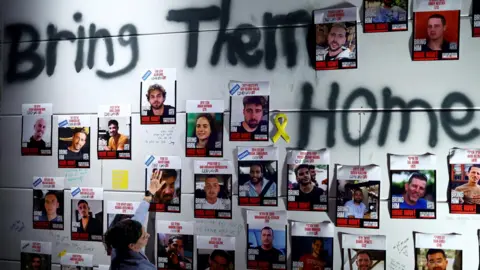

Reem continues her search in the wake of her son's disappearance. The fragmented records of Syria's missing children leave many parents in despair, as they navigate through a maze of orphanages, government offices, and the remnants of a regime predicated on secrecy and abuse.

The evidence presented by media investigations raises stark ethical queries about the responsibilities of international charities in conflict regions, especially regarding their duty to protect vulnerable populations from being exploited in broader political games. As parents like Reem pursue answers in the face of overwhelming bureaucratic barriers, the fate of countless children remains tragically uncertain.