The Black Hawk helicopter was ready for takeoff as it sliced through the heavy heat of the Colombian Amazon. I squeezed in with the Jungle Commandos, a police special operations unit initially trained by the British SAS in 1989. Heavily armed and ready for action, we knew the mission well and felt a surge of adrenaline; engaging with any part of the Colombian drug trade demands an acute readiness for confrontation.

As we flew over Putumayo, Colombia’s cocaine heartland nearing the Ecuador border, we spotted the telltale green of coca plantation thriving across a swath of land almost double the size of Greater London, a direct report from the United Nations indicating that Colombia accounts for around 70% of global cocaine production.

Resistance from criminal groups and former guerillas often complicates our missions, as we advanced into the area. Shortly after landing in a clearing, we encountered an operational cocaine lab buried among the banana trees, armed with essential chemicals and fresh coca leaves ready to be processed into cocaine paste.

Two individuals emerged from the brush—likely workers, their torn clothes hinting at poverty. When questioned, no arrests were made; this mission targets the architecture of drug trade, not its vulnerable foot soldiers—the desperate farmers.

After quickly assessing the site, commandos prepared to ignite the lab, sending a plume of black smoke billowing into the sky as we took off once more. According to an officer, there are reportedly 50 or 60 more labs lingering in this area. As we resumed our aerial reconnaissance, the commandos carried energy drinks, affirming their readiness for multiple operations within the day.

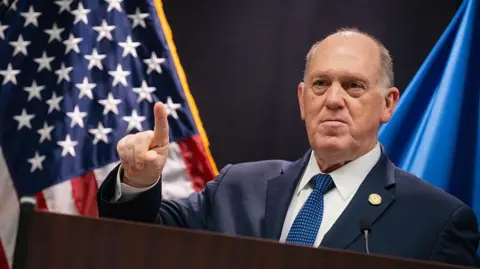

In recent political discourse, tensions rise as U.S. President Donald Trump criticizes Colombian President Gustavo Petro for insufficient action against drug trafficking. Yet Petro claims historic records in drug seizures have been achieved under his administration, despite growing production statistics. The ongoing war against narcotics continues to dominate the agenda for Petro and President Biden’s upcoming meeting in Washington, D.C.

Back at base, Major Cristhian Cedano Díaz summarized the ongoing difficulties succinctly, revealing drug labs can be rebuilt quickly after being destroyed. However, he argues these operations serve a critical function in diminishing the financial foundation of trafficking organizations, stressing that by targeting sites of production, they inflict substantial losses on criminal enterprises.

As the drug war evolves with criminals utilizing advanced technologies, this enduring battle damages both sides; from soldiers with casualties to farmers with disproportionately limited options, individuals like Javier, a coca farmer, reflect a disheartening reality against the backdrop of a surge in cocaine usage across Europe.

In facing a society ravaged by economic hardship and violence, Javier expresses his conflict. While he remains aware of the harm caused by his cultivation, survival instincts dominate, echoing a plea for economic support rather than threats of military action: understanding the reasons behind such desperate choices is essential for progress in the ongoing fight against drug trafficking.

As we flew over Putumayo, Colombia’s cocaine heartland nearing the Ecuador border, we spotted the telltale green of coca plantation thriving across a swath of land almost double the size of Greater London, a direct report from the United Nations indicating that Colombia accounts for around 70% of global cocaine production.

Resistance from criminal groups and former guerillas often complicates our missions, as we advanced into the area. Shortly after landing in a clearing, we encountered an operational cocaine lab buried among the banana trees, armed with essential chemicals and fresh coca leaves ready to be processed into cocaine paste.

Two individuals emerged from the brush—likely workers, their torn clothes hinting at poverty. When questioned, no arrests were made; this mission targets the architecture of drug trade, not its vulnerable foot soldiers—the desperate farmers.

After quickly assessing the site, commandos prepared to ignite the lab, sending a plume of black smoke billowing into the sky as we took off once more. According to an officer, there are reportedly 50 or 60 more labs lingering in this area. As we resumed our aerial reconnaissance, the commandos carried energy drinks, affirming their readiness for multiple operations within the day.

In recent political discourse, tensions rise as U.S. President Donald Trump criticizes Colombian President Gustavo Petro for insufficient action against drug trafficking. Yet Petro claims historic records in drug seizures have been achieved under his administration, despite growing production statistics. The ongoing war against narcotics continues to dominate the agenda for Petro and President Biden’s upcoming meeting in Washington, D.C.

Back at base, Major Cristhian Cedano Díaz summarized the ongoing difficulties succinctly, revealing drug labs can be rebuilt quickly after being destroyed. However, he argues these operations serve a critical function in diminishing the financial foundation of trafficking organizations, stressing that by targeting sites of production, they inflict substantial losses on criminal enterprises.

As the drug war evolves with criminals utilizing advanced technologies, this enduring battle damages both sides; from soldiers with casualties to farmers with disproportionately limited options, individuals like Javier, a coca farmer, reflect a disheartening reality against the backdrop of a surge in cocaine usage across Europe.

In facing a society ravaged by economic hardship and violence, Javier expresses his conflict. While he remains aware of the harm caused by his cultivation, survival instincts dominate, echoing a plea for economic support rather than threats of military action: understanding the reasons behind such desperate choices is essential for progress in the ongoing fight against drug trafficking.