The Nigerian family who have spent five decades as volunteer grave-diggers

For more than 50 years, one family has dedicated itself to caring for the biggest graveyard in Nigeria's northern city of Kaduna - much to the gratitude of other residents who do not fancy the job of dealing with the dead. Until a few weeks ago, they worked without formal pay, digging graves, washing corpses, and tending to the vast cemetery, receiving only small donations from mourners for their labor. The expansive Tudun Wada Cemetery was designated for Muslim residents of the city by authorities about a century ago.

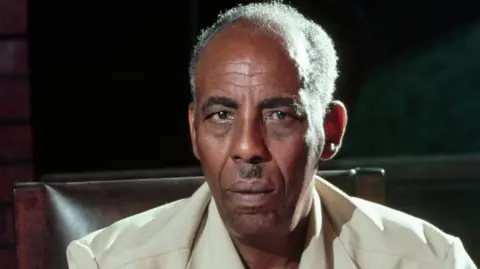

The Abdullahi family became involved in the 1970s when two brothers, Ibrahim and Adamu, began working there. The two siblings now lie beneath the soil in the graveyard, leaving their sons as the cemetery's main custodians. "Their teachings to us, their children, was that God loves the service and would reward us for it even if we don't get any worldly gains," Magaji, Ibrahim Abdullahi's oldest son, told the BBC. At 58, he oversees operations along with his two younger cousins, Abdullahi, 50, and Aliyu, 40. They work shifts from 07:00 for a grueling 12-hour day, seven days a week.

Calls generally come in from relatives or local imams when someone passes away, prompting immediate action from the team. Once at a death scene, they prepare the body, which involves washing and wrapping it in a traditional shroud. Precise measurements are sent back to the others, who dig graves often over six feet deep and on occasion take two or more hours when working in rocky areas.

Operating in the sweltering heat, they can typically dig around a dozen graves each day. “Today alone we have dug eight graves and it’s not even noon," Abdullahi expressed, detailing the physically demanding task. The trio's job has proven especially challenging during times of religious violence in Kaduna, where communities exist on either side of the city’s river.

Typically, funerals are conducted shortly after death, with community members often attending alongside mosque prayers. Once the body is interred, the site is marked humbly, adhering to Islamic customs discouraging ostentation. Donations are requested from mourners, generally by the oldest worker, 72-year-old Inuwa Mohammed, who speaks highly of the Abdullahi family's legacy.

However, the money collected seldom suffices for them to thrive. To sustain themselves, they maintain a small farm, considering the limitations in maintenance and security at the cemetery. The situation has changed dramatically following a recent visit by the BBC, resulting in the local council chairman choosing to formally employ the family.

"They deserve it, given the massive work they do every day," Rayyan Hussain shared. The newly appointed salaries, while below the national minimum wage, symbolize a recognition of their contributions. The chairman promises to improve conditions further, outlining plans that include installing lights and repairing the cemetery's fencing.

For the Abdullahi family, this assistance not only supports them financially but also helps preserve the heritage and service that they have dutifully provided for decades. Magaji hopes that one day, one of his 23 children will follow in their footsteps and become a custodian of the cemetery.

For more than 50 years, one family has dedicated itself to caring for the biggest graveyard in Nigeria's northern city of Kaduna - much to the gratitude of other residents who do not fancy the job of dealing with the dead. Until a few weeks ago, they worked without formal pay, digging graves, washing corpses, and tending to the vast cemetery, receiving only small donations from mourners for their labor. The expansive Tudun Wada Cemetery was designated for Muslim residents of the city by authorities about a century ago.

The Abdullahi family became involved in the 1970s when two brothers, Ibrahim and Adamu, began working there. The two siblings now lie beneath the soil in the graveyard, leaving their sons as the cemetery's main custodians. "Their teachings to us, their children, was that God loves the service and would reward us for it even if we don't get any worldly gains," Magaji, Ibrahim Abdullahi's oldest son, told the BBC. At 58, he oversees operations along with his two younger cousins, Abdullahi, 50, and Aliyu, 40. They work shifts from 07:00 for a grueling 12-hour day, seven days a week.

Calls generally come in from relatives or local imams when someone passes away, prompting immediate action from the team. Once at a death scene, they prepare the body, which involves washing and wrapping it in a traditional shroud. Precise measurements are sent back to the others, who dig graves often over six feet deep and on occasion take two or more hours when working in rocky areas.

Operating in the sweltering heat, they can typically dig around a dozen graves each day. “Today alone we have dug eight graves and it’s not even noon," Abdullahi expressed, detailing the physically demanding task. The trio's job has proven especially challenging during times of religious violence in Kaduna, where communities exist on either side of the city’s river.

Typically, funerals are conducted shortly after death, with community members often attending alongside mosque prayers. Once the body is interred, the site is marked humbly, adhering to Islamic customs discouraging ostentation. Donations are requested from mourners, generally by the oldest worker, 72-year-old Inuwa Mohammed, who speaks highly of the Abdullahi family's legacy.

However, the money collected seldom suffices for them to thrive. To sustain themselves, they maintain a small farm, considering the limitations in maintenance and security at the cemetery. The situation has changed dramatically following a recent visit by the BBC, resulting in the local council chairman choosing to formally employ the family.

"They deserve it, given the massive work they do every day," Rayyan Hussain shared. The newly appointed salaries, while below the national minimum wage, symbolize a recognition of their contributions. The chairman promises to improve conditions further, outlining plans that include installing lights and repairing the cemetery's fencing.

For the Abdullahi family, this assistance not only supports them financially but also helps preserve the heritage and service that they have dutifully provided for decades. Magaji hopes that one day, one of his 23 children will follow in their footsteps and become a custodian of the cemetery.