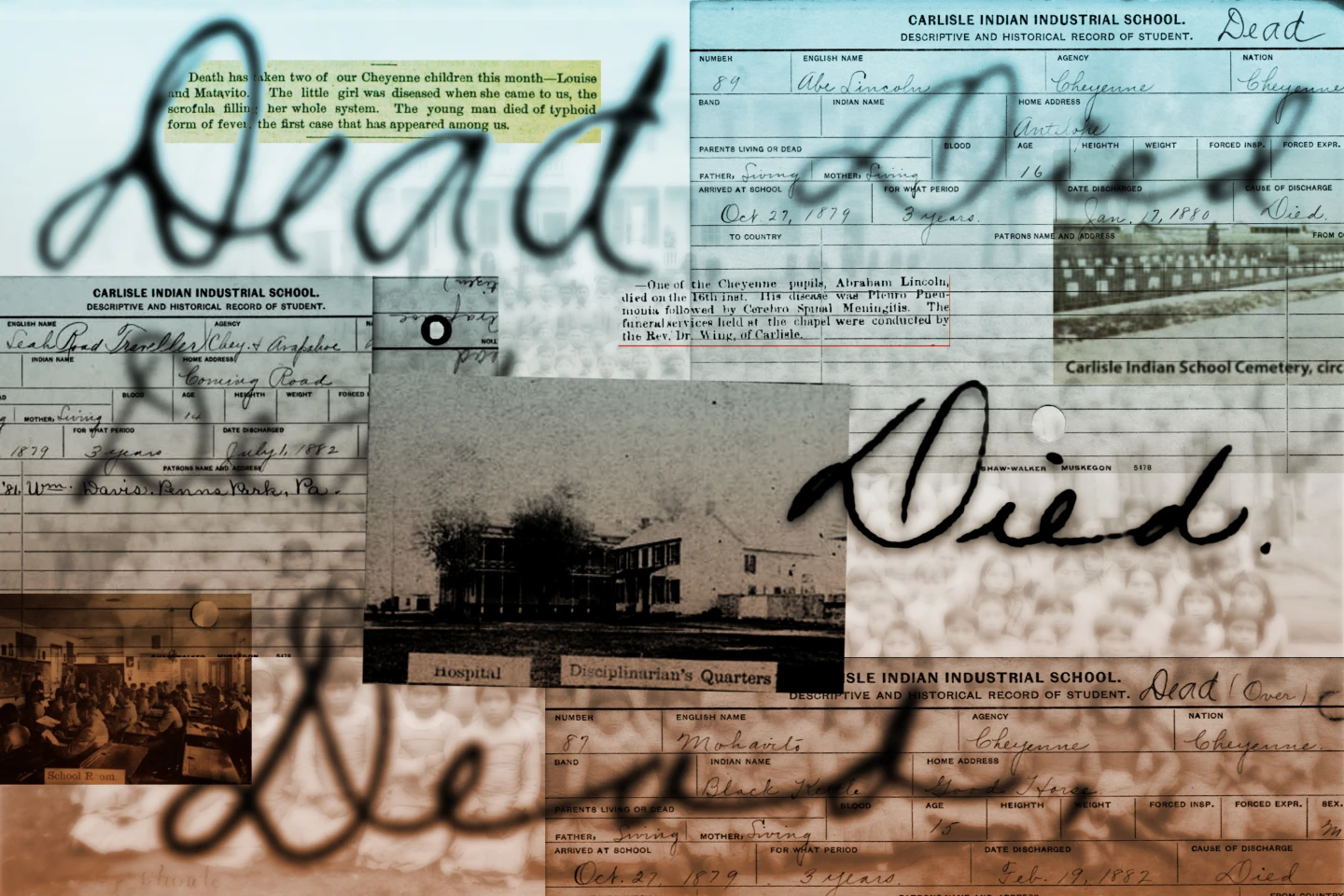

In October 1879, Matavito Horse and Leah Road Traveler were among the first students to arrive at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, a troubling institution aimed at erasing Native American identities. Their tragic stories, along with those of 15 other students, were brought to attention when their remains were finally returned to their tribes after being exhumed from a cemetery in Pennsylvania.

Last month, the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma conducted burial ceremonies for their lost children, marking a critical moment in their journey for justice and healing. This repatriation was a significant achievement for the tribes, who have consistently fought for the recognition and return of their descendants.

The Carlisle school, which operated from 1879 to 1918, housed around 7,800 students from over 100 different tribes. The atmosphere was rife with trauma, as students experienced loss of family, culture, and identity. Historical records indicate that many of these children died from various diseases and harsh conditions without adequate care.

As recent investigations reveal, the impact of these institutions continues to haunt Native American communities. Dark secrets from the past about abuse and neglect in boarding schools are now being acknowledged, reflecting on the emotional scars that survivors carry.

Historians and tribal leaders have brought attention to the female students and their artistic talents, contributing to the identity of their communities. Elsie Davis, a promising artist among the repatriated students, is remembered for her works even after her untimely death.

Continuing efforts for repatriation require not only resolve from the tribal nations but also accountability from the U.S. government and churches involved. As the process of identifying remains unfolds, it showcases the complexities of reconciliation and remembrance in the pursuit of justice for Indigenous peoples.