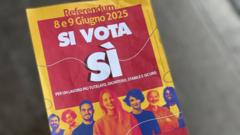

Sonny Olumati, at 39, embodies the plight of many born in Italy but lacking citizenship. Despite living in Rome his entire life, the dancer and activist is seen as Nigerian in the eyes of the law, reliant solely on residence permits. "This feeling of being rejected by your own country is painful," he expressed, urging support for a "Yes" vote in the upcoming referendum that would shorten the citizenship application timeline from 10 years to 5. This change reflects a much-needed update aligning Italy's laws with wider European practices.

Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, however, opposes the referendum, touting the current system as "excellent" and encouraging a boycott of the polling, suggesting beach outings instead. This lack of engagement highlights the complex emotional landscape of citizenship in Italy, where a significant number of migrants legally contribute to society yet remain excluded from the rights associated with citizenship, including the vote.

The context of this referendum sheds light on a longstanding tension in Italy's citizenship discourse. With rising migration from North Africa and stringent immigration controls, the government seeks to balance the needs of its aging population against the increasing inflow of foreign workers. Supporters of the referendum, like Carla Taibi from the More Europe party, argue it is crucial for legal residents' children and others who have entrenched their lives in Italy to secure citizenship more efficiently.

The stakes are high, with up to 1.4 million potential new citizens eligible should the referendum pass. Advocacy groups argue this reform is essential for their recognition as rightful members of Italian society. Yet the political landscape complicates the conversation; the current administration's reluctance to fully support the referendum raises questions about underlying societal attitudes toward race and immigration.

Sonny's struggles are echoed by others, like Insaf Dimassi, who articulates the intense frustration of living in a state of invisibility—unrecognized and unrepresented despite having grown up in Italy. “It’s not about meritocracy; we deserve to be seen as part of this country,” she asserts.

As the referendum looms, calls for participation emerge, notably from students in Rome who advocate for recognition and voting rights through public displays. Yet, with minimal media coverage and a government boycott, achieving the necessary turnout of over 50 percent poses a significant challenge.

Sonny remains resolute, asserting that whether the vote succeeds or fails, the pursuit for acknowledgment and belonging within Italy will continue. "This is just the beginning," he reflects, emphasizing the pressing need for a broader conversation about the identities of migrants in Italy.

Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, however, opposes the referendum, touting the current system as "excellent" and encouraging a boycott of the polling, suggesting beach outings instead. This lack of engagement highlights the complex emotional landscape of citizenship in Italy, where a significant number of migrants legally contribute to society yet remain excluded from the rights associated with citizenship, including the vote.

The context of this referendum sheds light on a longstanding tension in Italy's citizenship discourse. With rising migration from North Africa and stringent immigration controls, the government seeks to balance the needs of its aging population against the increasing inflow of foreign workers. Supporters of the referendum, like Carla Taibi from the More Europe party, argue it is crucial for legal residents' children and others who have entrenched their lives in Italy to secure citizenship more efficiently.

The stakes are high, with up to 1.4 million potential new citizens eligible should the referendum pass. Advocacy groups argue this reform is essential for their recognition as rightful members of Italian society. Yet the political landscape complicates the conversation; the current administration's reluctance to fully support the referendum raises questions about underlying societal attitudes toward race and immigration.

Sonny's struggles are echoed by others, like Insaf Dimassi, who articulates the intense frustration of living in a state of invisibility—unrecognized and unrepresented despite having grown up in Italy. “It’s not about meritocracy; we deserve to be seen as part of this country,” she asserts.

As the referendum looms, calls for participation emerge, notably from students in Rome who advocate for recognition and voting rights through public displays. Yet, with minimal media coverage and a government boycott, achieving the necessary turnout of over 50 percent poses a significant challenge.

Sonny remains resolute, asserting that whether the vote succeeds or fails, the pursuit for acknowledgment and belonging within Italy will continue. "This is just the beginning," he reflects, emphasizing the pressing need for a broader conversation about the identities of migrants in Italy.