Brazil's new development law has raised significant concerns about the future of the Amazon rainforest, as a UN expert warns of potentially grave environmental harm and human rights violations. Astrid Puentes Riaño, a special rapporteur, stated that the legislation represents a "rollback for decades" of existing protections and highlighted critical implications for the environment just ahead of Brazil's hosting of the COP30 climate summit later this year.

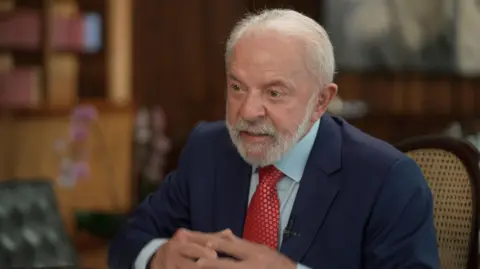

The Brazilian Congress recently passed measures designed to streamline environmental licensing for various infrastructure projects, including roads and energy developments. However, this law has yet to receive formal approval from President Lula da Silva. Critics, referring to the legislation as the "devastation bill," argue it could foster environmental abuses and lead to increased deforestation.

Proponents of the bill assert that simplifying the licensing process will help reduce bureaucratic delays and give businesses clarity in their operations. A notable change allows some developers to self-declare their environmental impacts via a simplified online form for lesser projects. Critics, however, view this as a significant concern, fearing it will exempt critical projects like mining from thorough assessments.

Riaño emphasized her worries that such relaxed regulations may not adequately address the environmental impacts, particularly in the Amazon region. She argued the plans to automatically renew licenses could facilitate deforestation without comprehensive assessments. This, combined with existing pressures from agriculture and mining, paints a troubling picture for the rainforest.

Recent analysis indicates a surge in deforestation within the Amazon, exacerbated by drought and wildfires. Under the new regulations, environmental authorities would be given a limited timeframe of one year—extendable to two—to decide on licensing, after which automatic approvals may occur.

While advocates tout the bill as a means to support economic growth and foster renewable energy initiatives, critics express that the weakening of environmental safeguards could lead to catastrophic ecological consequences and infringe on indigenous rights. UN experts have raised alarms that the expedited assessments may limit public participation and jeopardize human rights.

The legislation has passed both the Senate and Chamber of Deputies and is now awaiting the president's decision, with Lula da Silva having until August 8 to approve or veto the law. The Environment Minister, Marina Silva, has publicly condemned the bill, suggesting it represents a significant threat to Brazil's environmental integrity. Even if the president chooses to veto, the conservative congress may attempt to override this decision.

Brazil's Climate Observatory has described the proposed legislation as the largest environmental setback since the nation's military dictatorship, which saw rampant deforestation and the displacement of many indigenous communities. Riaño noted that the implications of this law could affect more than 18 million hectares, equivalent to the size of Uruguay. The stakes for the Amazon and its diverse ecosystems are incredibly high.

The Brazilian Congress recently passed measures designed to streamline environmental licensing for various infrastructure projects, including roads and energy developments. However, this law has yet to receive formal approval from President Lula da Silva. Critics, referring to the legislation as the "devastation bill," argue it could foster environmental abuses and lead to increased deforestation.

Proponents of the bill assert that simplifying the licensing process will help reduce bureaucratic delays and give businesses clarity in their operations. A notable change allows some developers to self-declare their environmental impacts via a simplified online form for lesser projects. Critics, however, view this as a significant concern, fearing it will exempt critical projects like mining from thorough assessments.

Riaño emphasized her worries that such relaxed regulations may not adequately address the environmental impacts, particularly in the Amazon region. She argued the plans to automatically renew licenses could facilitate deforestation without comprehensive assessments. This, combined with existing pressures from agriculture and mining, paints a troubling picture for the rainforest.

Recent analysis indicates a surge in deforestation within the Amazon, exacerbated by drought and wildfires. Under the new regulations, environmental authorities would be given a limited timeframe of one year—extendable to two—to decide on licensing, after which automatic approvals may occur.

While advocates tout the bill as a means to support economic growth and foster renewable energy initiatives, critics express that the weakening of environmental safeguards could lead to catastrophic ecological consequences and infringe on indigenous rights. UN experts have raised alarms that the expedited assessments may limit public participation and jeopardize human rights.

The legislation has passed both the Senate and Chamber of Deputies and is now awaiting the president's decision, with Lula da Silva having until August 8 to approve or veto the law. The Environment Minister, Marina Silva, has publicly condemned the bill, suggesting it represents a significant threat to Brazil's environmental integrity. Even if the president chooses to veto, the conservative congress may attempt to override this decision.

Brazil's Climate Observatory has described the proposed legislation as the largest environmental setback since the nation's military dictatorship, which saw rampant deforestation and the displacement of many indigenous communities. Riaño noted that the implications of this law could affect more than 18 million hectares, equivalent to the size of Uruguay. The stakes for the Amazon and its diverse ecosystems are incredibly high.