When my mother informed me at 16 that we were heading to Ghana for summer holidays, I trusted her completely. I assumed it would be a short, carefree trip. However, a month into our stay, she revealed a shocking truth: I wasn't returning to London until I had reformed and earned enough GCSEs to continue my education.

This experience mirrored that of a British-Ghanaian teenager who recently sought legal action against his parents for sending him to school in Ghana. They communicated a fear for his safety, expressing a desire to shield him from a potential violent fate in London. My mother, a primary school teacher, shared similar worries. After being expelled from two high schools in Brent and associating with the wrong crowd, I was headed down a dangerous path. Many of my friends from that time ended up in prison for serious crimes.

Initially, I felt that being sent to Ghana was akin to a prison sentence. I can relate to the teenager's expression of feeling like he was "living in hell." Yet, as I matured, I recognized that my mother's intervention was a blessing in disguise.

Unlike the boy who took his parents to court, I didn’t attend a boarding school. Instead, my mother arranged for me to stay with her brothers, who kept a close watch over me. I began my journey with my Uncle Fiifi in Dansoman, near Accra. The adjustment was overwhelming. In London, I enjoyed independence, but in Ghana, I woke up at 5 AM to sweep the courtyard and wash vehicles.

My rebellious streak hit a low when I attempted to steal my aunt's car, leading to a fateful crash that could have ended my life in military detention. This reckless act was a turning point in my life.

Life in Ghana also imparted discipline. Washing clothes by hand and preparing meals from scratch made me appreciate the effort involved. The experience instilled patience, as Ghanaian cooking required time and care, contrasting sharply with the convenience of fast food in London.

My uncles wisely opted not to send me to elite schools but enrolled me in a local secondary institution, Accra Academy, where I received personalized tuition. While the language of instruction remained English, I immersed myself in the local dialects and found that I could adapt quickly.

The academic rigor of the Ghanaian education system challenged me in new ways. I earned five GCSEs with respectable grades, a feat I once considered impossible. The values embedded in Ghanaian culture—like respecting elders and valuing community—shaped my character and resilience significantly.

Though the first 18 months were the hardest, filled with tensions and restrictions, I ultimately transitioned from viewing Ghana as a cage to embracing it as a home. Similarly, fellow expatriate Michael Adom expressed a bittersweet nostalgia for his own journey back to Ghana, emphasizing how, despite initial loneliness, it molded him into a man.

While I initially struggled with homesickness—there were even attempts to fly back to London—the insistence on adapting led to my growth. By my third year, I appreciated Ghanaian food, culture, and community profoundly. I came to love waakye, a traditional dish, and found comfort in the warm-heartedness of the local people.

Reflecting on my mother's sacrifice, especially after her recent passing, I see how her decision saved me from a likely life of crime. Had I remained in London, I would have faced substantial negative repercussions. Instead, I enrolled in college at 20, branching into media, ultimately finding my place at BBC Radio 1Xtra.

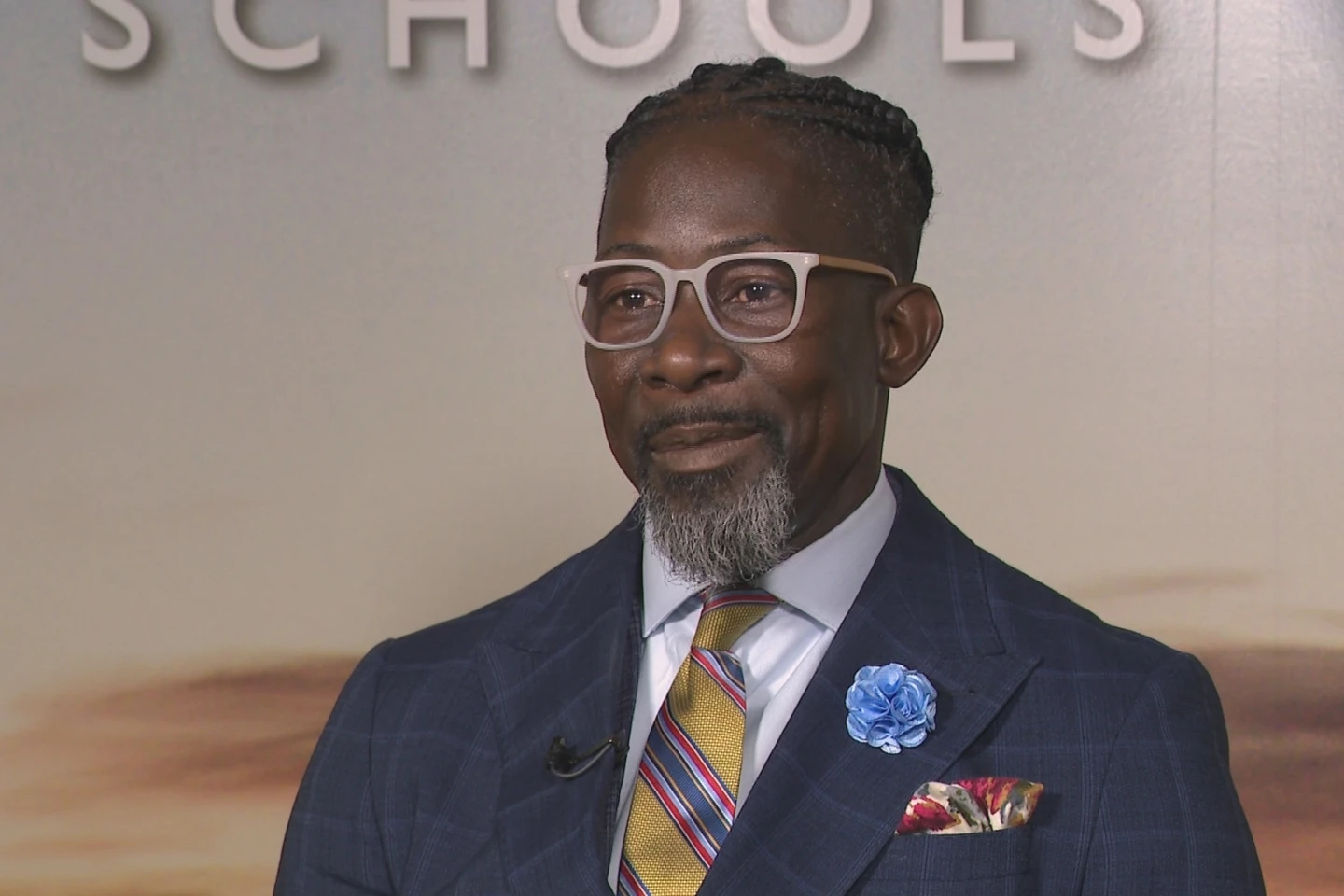

While not every child's experience will be as transformative, my time in Ghana opened doors to education, discipline, and cultural identity that shaped my future. For that, I am eternally grateful to my mother, my uncles, and a country that guided me toward success. Mark Wilberforce is now a freelance journalist based in London and Accra.