PHOENIX (AP) — Ahead of the 2024 presidential election, U.S. Army veteran Sae Joon Park reflects on a warning he received from an immigration officer: the potential for deportation if Donald Trump were to return to power.

At the age of seven, Park immigrated to the U.S. from Seoul, South Korea. He enlisted in the Army at 19 and earned a Purple Heart while serving in Panama. However, after leaving the military, he faced battles with PTSD that led to substance abuse challenges.

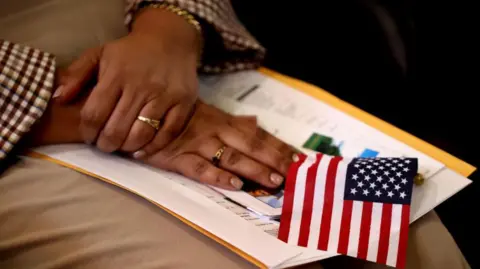

In 2009, following a drug-related arrest, Park was eventually ordered to be deported. Thankfully, as a veteran, he was granted deferred action, enabling him to remain in the U.S. under the condition of regular check-ins with immigration officials.

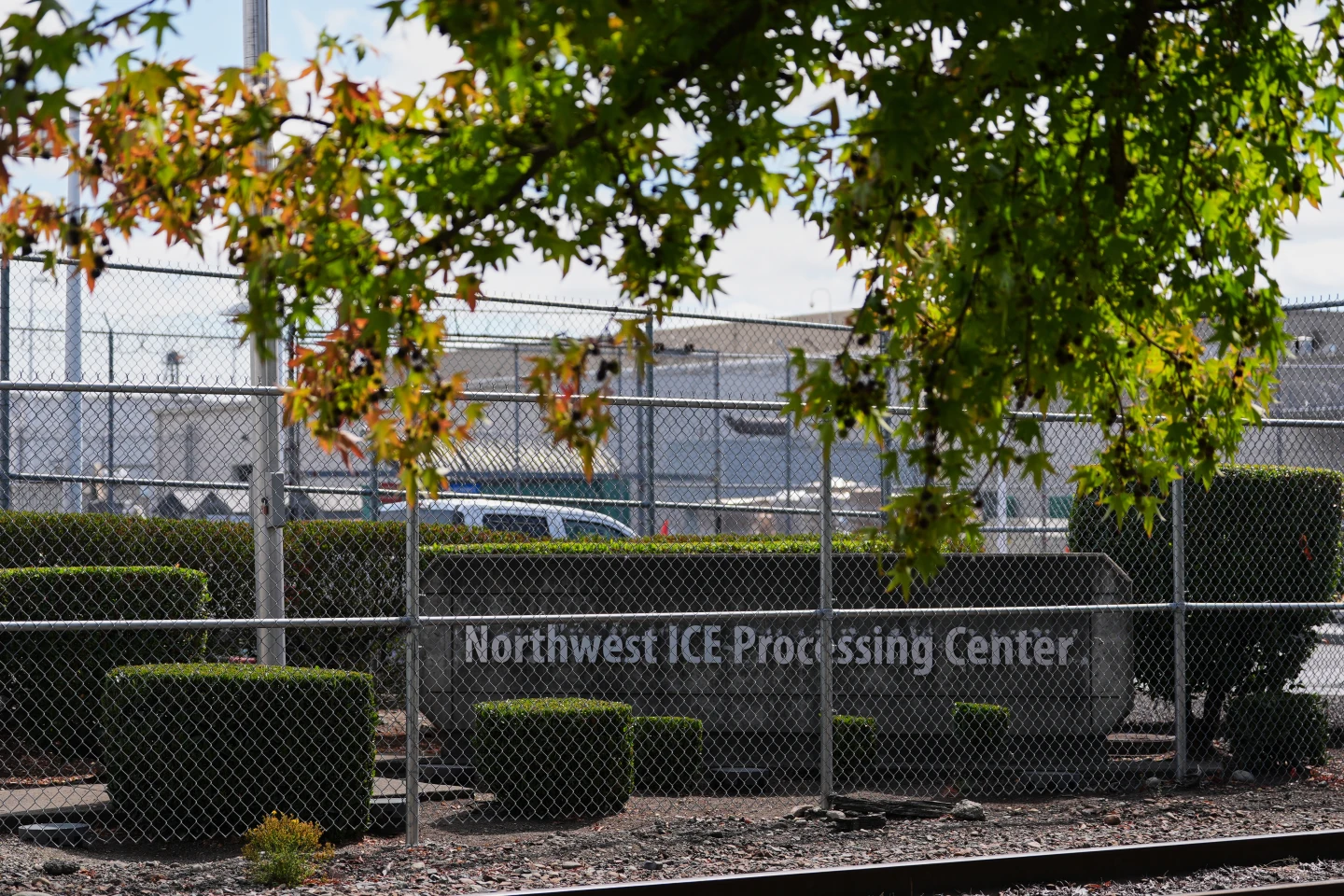

That arrangement lasted 14 years, during which Park built a life in Honolulu and raised his children. However, upon attending a routine appointment in June, he was shocked to discover that a removal order had been placed against him. Fearing extended detention, Park made the heart-wrenching choice to self-deport.

“They allowed me to join, serve the country – front line, taking bullets for this country. That should mean something,” he stressed, lamenting the treatment veterans like himself receive.

During Trump’s first term, a slew of immigration policies were enacted that affected even those typically shielded from scrutiny — veterans and active-duty service members. The administration looked to limit pathways for immigrant service members seeking citizenship, attempting to complicate the enlistment of green card holders, though these measures were often successful.

Currently, experts and veterans argue that the immigration policies once again target servicemen, with many fearing deportation. “President Trump campaigned on promises of mass deportations, and he didn’t exempt military members, veterans and their families,” said retired Lt. Col. Margaret Stock, emphasizing potential damage to military readiness and national security.

The Biden administration initially implemented a policy considering a non-citizen’s military service as a mitigating factor in deportation cases. However, in April, this policy was rescinded, stating military service alone does not provide assurance from enforcement actions, leaving concerned veterans vulnerable.

Park is not alone; other veterans, like Narciso Barranco, a father of U.S. Marines, have also faced detainment under these evolving policies. Barranco’s son highlighted the broader implications of these deportations on families and communities.

Attempts to quantify the number of veterans affected by these policies remain elusive. Federal lawmakers have called for transparency on this matter, with estimates suggesting as many as 10,000 veterans may have been deported.

Legislation aimed at protecting immigrant service members and their families has been introduced, and U.S. Sen. Tammy Duckworth pushed for reforms, asserting that honoring veterans who wore the nation’s uniform is paramount.

As of early 2024, more than 40,000 foreign nationals are serving in various capacities within the U.S. Armed Forces. Despite policies allowing expedited naturalization for serving during designated periods of hostility, veterans continue to encounter hurdles when facing the threat of deportation.

Instances like Park’s reflect systemic failures in supporting those who have sacrificed for the nation. After being deported back to South Korea, Park struggles to adjust to a life in a land he barely remembers. “It’s a whole new world,” he admitted, sharing his fears about never returning to the U.S.

With ongoing public support behind him, Park's legal team is advocating to annul his deportation order, yet hope remains dim as he grapples with the reality of being distanced from the country he served.