Parts of Australia’s Great Barrier Reef have experienced the most significant coral cover decline since monitoring began nearly four decades ago, according to a recent report from the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS). Both the northern and southern branches of this iconic reef system suffered extensive coral bleaching, marking an alarming trend. Recent months have seen reefs impacted by tropical cyclones and outbreaks of the crown-of-thorns starfish, which consumes coral. However, the primary concern remains climate change and the heat stress it causes.

The AIMS report warns that the reef might be approaching a tipping point, where coral cannot recover quickly enough after extreme events, leading to an uncertain and volatile future for this crucial habitat. AIMS has been conducting surveys to assess the health of the reef, studying 124 coral reefs between August 2024 and May 2025; they have been monitoring its status since 1986.

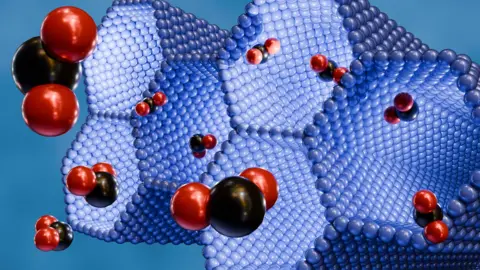

Often referred to as the world's largest living structure, the Great Barrier Reef stretches over 2,300 kilometers (1,429 miles) and supports a diverse ecosystem. Repeated bleaching events, primarily caused by rising ocean temperatures, have severely impacted the coral ecosystem, which is essential for sustaining about 25% of all marine life.

When water temperatures rise too high, coral becomes stressed, leading to bleaching, where it turns white. While coral can recover, it requires sufficient time, ideally years, in cooler temperatures. The latest heat stress events have prompted a significant bleaching around the Great Barrier Reef, with the ongoing incident being the sixth instance since 2016. Compounding the situation, natural weather patterns such as El Niño can influence these bleaching occurrences.

According to the AIMS report, the levels of heat stress on the reef have reached unprecedented levels, causing a widespread and severe bleaching response. Recovery of the corals is contingent on successful reproduction and a stabilization of environmental conditions.

The AIMS data indicates that the most affected coral species were the Acropora, which are especially vulnerable to heat stress and favored by the crown-of-thorns starfish. Dr. Mike Emslie of AIMS emphasized the importance of fighting to protect the Great Barrier Reef, highlighting its inherent ability to recover if given a chance.

Despite some success from the Australian government's culling program, which has helped eliminate over 50,000 crown-of-thorns starfish, the reef continues to face significant challenges. Richard Leck of WWF remarked that the findings indicate the reef is under extreme stress, warning that without rapid climate action, it risks reaching a point of irreversible damage, similar to other global coral reefs that have already collapsed.

The Great Barrier Reef has been a UNESCO World Heritage site for over 40 years, but the organization has flagged it as "in danger" due to the ongoing threats of climate change and pollution.