India is grappling with a serious healthcare paradox, where deadly superbugs flourish due to antimicrobial resistance, while many patients die from infections that could be treatable if they had access to antibiotics. The latest research by the Global Antibiotic Research and Development Partnership (GARDP) reveals alarming statistics about the treatment of carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative (CRGN) infections, particularly in India, which accounted for a significant proportion of total cases studied across low- and middle-income countries.

This study, published in The Lancet Infectious Diseases journal, shows that of the 1.5 million cases studied, only 6.9% of patients received the appropriate treatment. India, which procured 80% of the antibiotics for these infections, managed to treat a mere 7.8% of patients requiring care. CRGN bacteria, known for causing severe infections like UTIs, pneumonia, and food poisoning, pose severe threats to vulnerable populations, including newborns and elderly patients in hospitals.

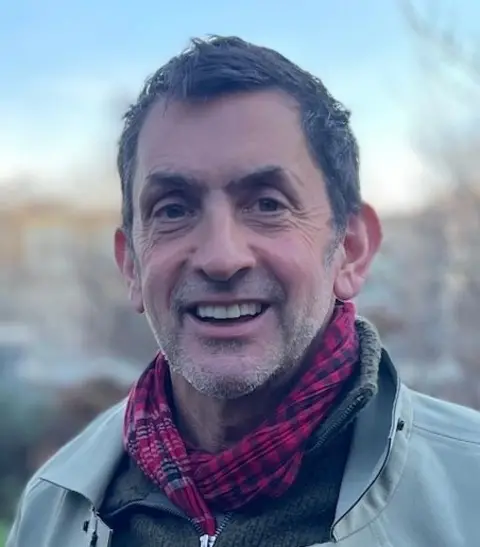

Dr. Abdul Gaffar, an infectious disease consultant in Chennai, highlights the tragic reality where patients often arrive with infections resistant to known treatments, leading to preventable deaths. The irony lies in the simultaneous narrative of antibiotic overuse globally; many people in poorer nations suffer without access to essential antibiotics needed to combat infections.

Dr. Jennifer Cohn, GARDP's Global Access Director, points out the critical gap in healthcare, emphasizing that while antibiotic stewardship is crucial, significant numbers of patients with drug-resistant infections are unable to access the treatments they require. The troubling study tracked intravenous drugs active against CRGN bacteria, finding that despite the need for approximately 1.5 million treatment courses, less than a tenth were procured in the overall studied regions.

Obstacles to accessing effective medications include the lack of diagnostic tools, insufficient health infrastructure, and the prohibitively high costs of antibiotics. Dr. Gaffar notes that those who have the means tend to overuse these critical drugs while those in impoverished situations remain without necessary treatment.

To improve the situation, enhanced affordability and stronger regulation are needed, including mandatory oversight for antibiotic prescriptions within hospitals to ensure correct usage. Research indicates that India has the potential to lead in the fight against antimicrobial resistance, leveraging its strong pharmaceutical market for the development of new antibiotics.

Building a strategic response, healthcare experts envision innovative solutions that involve collected data to identify treatment needs and gaps. Approaches such as the "hub-and-spoke model" in Kerala showcase promising efforts to allocate resources and support lower-tier facilities. Even collective procurement initiatives could mitigate costs similar to successful programs for cancer medications.

Without immediate and effective measures to address these issues, the foundation of modern medicine faces jeopardy. Ensuring timely access to the right antibiotics will not only allow for the safe provision of surgeries and cancer care but also restore the ability to manage infections commonly seen in practice.