In the early 2010s, a remarkable discovery unfolded in the French antiques market when two elaborate chairs, claimed to be owned by Marie Antoinette and allegedly linked to the Palace of Versailles, emerged. Stamped by the renowned 18th-century cabinetmaker Nicolas-Quinibert Foliot, these chairs drew considerable attention and were ultimately designated as "national treasures" by the French government in 2013, following interest from Versailles itself. However, the palace found their asking price excessive, leading to their sale to Qatari Prince Mohammed bin Hamad Al Thani for €2 million (£1.67 million).

A wave of high-value 18th Century furniture sightings had caught collectors’ eyes, including pieces attributed to notable figures of the French monarchy. Many ended up in Versailles’s collection, yet by 2016, a shocking revelation regarding these royal chairs sent ripples through the French antiques community—the chairs were all forgeries.

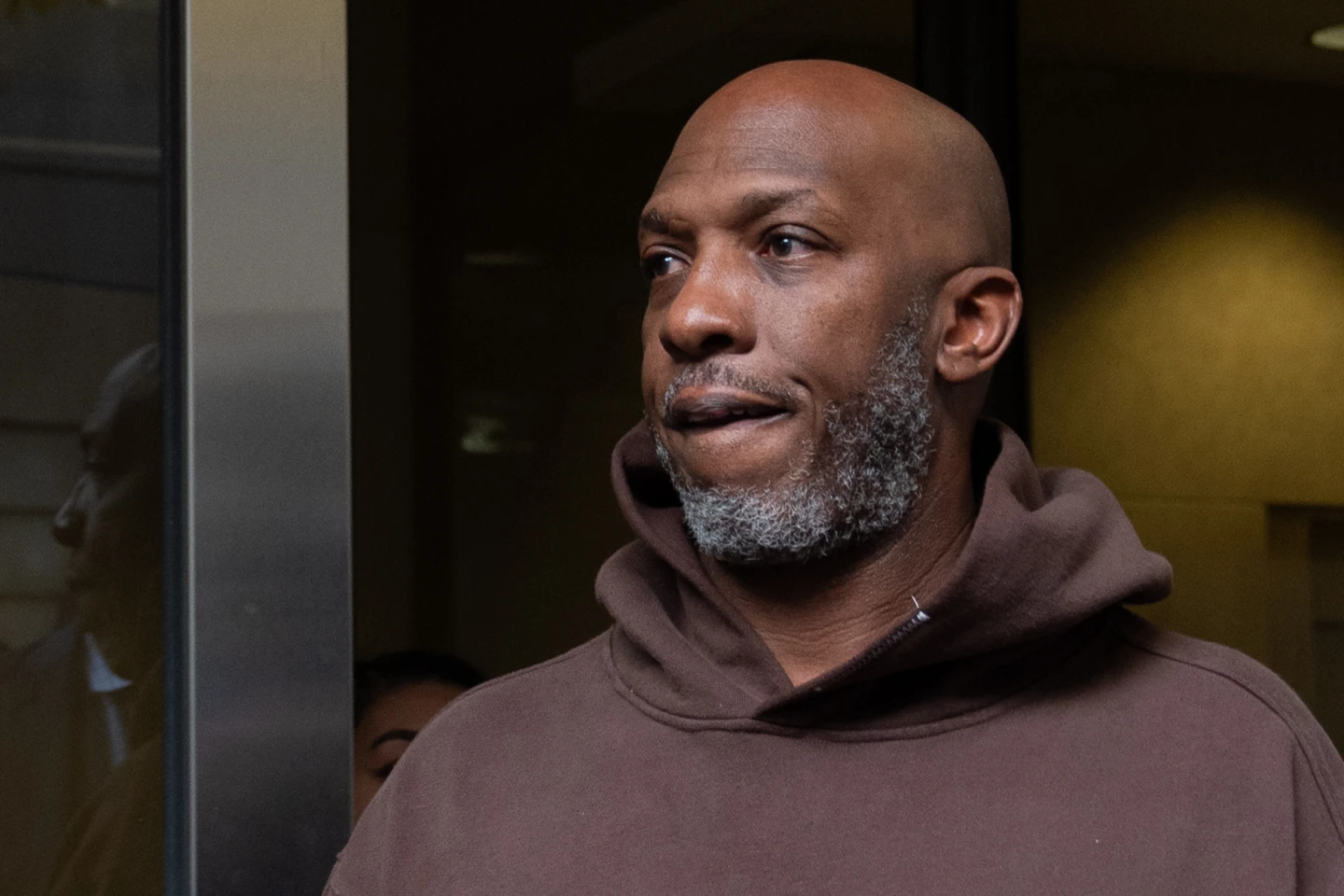

Antiques authority Georges "Bill" Pallot and acclaimed cabinetmaker Bruno Desnoues faced a court trial for their roles in orchestrating this massive fraud, which included charges of money laundering. They reportedly began their forgery venture in 2007 as an experiment, originally creating replicas of an armchair associated with Madame du Barry. Their success inspired them to replicate more pieces, leading to the extensive sale of fakes.

During the trial, Pallot, known for his authoritative knowledge of French 18th-century furniture, detailed how they fabricated these chairs using cheap harvested wood, applying techniques to age the materials and replicate historical finishes. They appended falsified stamps and sold the chairs through intermediaries.

Prosecutors believe Pallot and Desnoues profited over €3 million from the scam, while the two men contested that their total earnings were less than €700,000. The scandal escalated when the lavish lifestyle of a Portuguese handyman sparked investigations, eventually unraveling the facade.

While Pallot and Desnoues have confessed their guilt, the involvement of Galerie Kraemer and its director, Laurent Kraemer, remains contentious. They were charged with gross negligence for failing to authenticate the chairs sold to collectors, including Versailles. Despite the gallery claiming to be unsuspecting victims, the prosecution argued they should have utilized their resources to confirm authenticity given the high stakes involved.

This case serves as a wake-up call for the art market, emphasizing the need for stringent oversight and ethical standards in the antiques trade. As the accused prepare for further hearings, the implications of this fraud case echo beyond the courtroom, threatening the integrity of institutions built to preserve history.

A wave of high-value 18th Century furniture sightings had caught collectors’ eyes, including pieces attributed to notable figures of the French monarchy. Many ended up in Versailles’s collection, yet by 2016, a shocking revelation regarding these royal chairs sent ripples through the French antiques community—the chairs were all forgeries.

Antiques authority Georges "Bill" Pallot and acclaimed cabinetmaker Bruno Desnoues faced a court trial for their roles in orchestrating this massive fraud, which included charges of money laundering. They reportedly began their forgery venture in 2007 as an experiment, originally creating replicas of an armchair associated with Madame du Barry. Their success inspired them to replicate more pieces, leading to the extensive sale of fakes.

During the trial, Pallot, known for his authoritative knowledge of French 18th-century furniture, detailed how they fabricated these chairs using cheap harvested wood, applying techniques to age the materials and replicate historical finishes. They appended falsified stamps and sold the chairs through intermediaries.

Prosecutors believe Pallot and Desnoues profited over €3 million from the scam, while the two men contested that their total earnings were less than €700,000. The scandal escalated when the lavish lifestyle of a Portuguese handyman sparked investigations, eventually unraveling the facade.

While Pallot and Desnoues have confessed their guilt, the involvement of Galerie Kraemer and its director, Laurent Kraemer, remains contentious. They were charged with gross negligence for failing to authenticate the chairs sold to collectors, including Versailles. Despite the gallery claiming to be unsuspecting victims, the prosecution argued they should have utilized their resources to confirm authenticity given the high stakes involved.

This case serves as a wake-up call for the art market, emphasizing the need for stringent oversight and ethical standards in the antiques trade. As the accused prepare for further hearings, the implications of this fraud case echo beyond the courtroom, threatening the integrity of institutions built to preserve history.