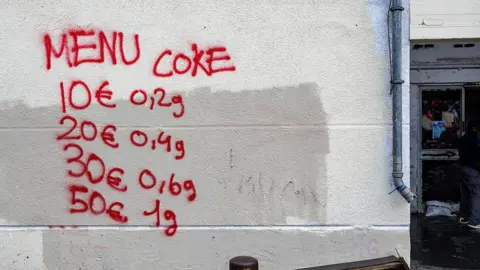

In parts of Luanda, fear grips the residents as memories of July's protests linger. Initiated by taxi drivers challenging soaring fuel costs, the demonstrations spiraled into violence, causing numerous fatalities and widespread arrests. Roads burned and shops were looted, marking one of the most significant displays of dissent in Angola since its civil war ended in 2002.

As the nation gears up to celebrate its 50th independence anniversary from Portugal, the protests have cast a shadow on the festivities, exposing the lingering plight of poverty and inequality despite Angola's vast oil wealth. In areas hardest hit by the unrest, residents remain hesitant to voice their thoughts, fearing repercussions from authorities amidst a backdrop of numerous arrests.

A young street vendor in Luanda reflected on the protests, stating, ‘We needed to make noise to wake those in power.’ This sentiment resonates as Angola grapples with a staggering youth unemployment rate of 54% against a backdrop of systemic issues post-civil war.

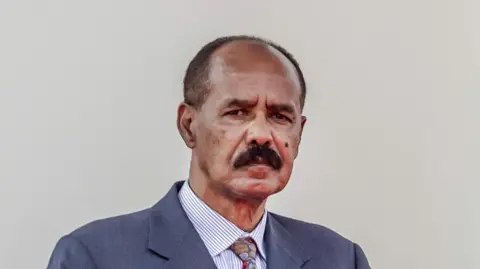

The sociologist Gilson Lázaro emphasizes that the protesters are predominantly the ‘dispossessed’, echoing sentiments of frustration felt by the youth towards a government they perceive as failing to address their needs. President João Lourenço's administration, which promised reforms, faces increasing criticism over its handling of economic issues and social unrest.

Protests such as those seen in July indicate an awakening political consciousness among Angolans—a prelude to possible unrest as the country approaches the next elections. Young voices, once muted by desperation, are increasingly using protests to express their grievances, highlighting the necessity for the government to avert future crises by addressing the root causes of inequality and dissatisfaction.

As the nation gears up to celebrate its 50th independence anniversary from Portugal, the protests have cast a shadow on the festivities, exposing the lingering plight of poverty and inequality despite Angola's vast oil wealth. In areas hardest hit by the unrest, residents remain hesitant to voice their thoughts, fearing repercussions from authorities amidst a backdrop of numerous arrests.

A young street vendor in Luanda reflected on the protests, stating, ‘We needed to make noise to wake those in power.’ This sentiment resonates as Angola grapples with a staggering youth unemployment rate of 54% against a backdrop of systemic issues post-civil war.

The sociologist Gilson Lázaro emphasizes that the protesters are predominantly the ‘dispossessed’, echoing sentiments of frustration felt by the youth towards a government they perceive as failing to address their needs. President João Lourenço's administration, which promised reforms, faces increasing criticism over its handling of economic issues and social unrest.

Protests such as those seen in July indicate an awakening political consciousness among Angolans—a prelude to possible unrest as the country approaches the next elections. Young voices, once muted by desperation, are increasingly using protests to express their grievances, highlighting the necessity for the government to avert future crises by addressing the root causes of inequality and dissatisfaction.